New stabilized FastPrep-CLEAs for sialic acid synthesis

María Inmaculada García-García, Agustín Sola-Carvajal, Guiomar Sánchez-Carrón, Francisco García-Carmona, Álvaro Sánchez-Ferrer

Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology-A, Faculty of Biology, University of Murcia, Campus Espinardo, E-30100 Murcia, Spain

Bioresource Technology 102 (2011) 6186–6191, journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biortech

Abstract

N-acetyl-D-neuraminic acid aldolase, a key enzyme in the biotechnological production of N-acetyl-D-neuraminic acid (sialic acid) from N-acetyl-D-mannosamine and pyruvate, was immobilized as cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs) by precipitation with 90% ammonium sulfate and crosslinking with 1% glutaraldehyde. Because dispersion in a reciprocating disruptor (FastPrep) was only able to recover 40% of the activity, improved CLEAs were then prepared by co-aggregation of the enzyme with 10 mg/mL bovine serum albumin followed by a sodium borohydride treatment and final disruption by FastPrep (FastPrep- CLEAs). This produced a twofold increase in activity up to 86%, which is a 30% more than that reported for this aldolase in cross-linked inclusion bodies (CLIBs). In addition, these FastPrep-CLEAs presented remarkable biotechnological features for Neu5Ac synthesis, including, good activity and stability at alkaline pHs, a high KM for ManNAc (lower for pyruvate) and good operational stability. These results reinforce the practicability of using FastPrep-CLEAs in biocatalysis, thus reducing production costs and favoring reusability.

© 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Article info

Article history:

Received 22 December 2010

Received in revised form 4 February 2011

Accepted 5 February 2011

Available online 3 March 2011

Keywords:

CLEAs

Sialic acid

N-acetylneuraminate lyase

Kinetic parameters

Synthesis

1. Introduction

Although biocatalysts are useful tools for a green and sustainable industry (Sheldon, 2010), their synthetic application is often limited by production and operating costs. Numerous efforts have been devoted to producing robust immobilized catalysts by binding enzyme to a solid carrier, by encapsulation in a organic or inorganic polymeric gel, or by cross-linking of the protein molecules in the form of cross-linked enzyme crystals (CLECs) or cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs) (Roessl et al., 2010). The latter method not only avoids the inherent dilution of the enzyme in the presence of an inert carrier, but also the need for a highly purified enzyme to start the laborious screening to identify conditions of crystallization that produce catalytic crystals (CLECs). A simple way of preparing CLEAs consists of protein precipitation into an aqueous solution by adding a salt, a water-miscible organic solvent or a polymer (Gupta et al., 2009). In a subsequent step, physical aggregates of the enzyme are cross-linked with a bifunctional agent, the agent of choice being glutaraldehyde, since it is inexpensive and readily available in commercial quantities (Sheldon, 2007). Such cross-linking produces CLEAs, in which the catalytic activity of an individual enzyme is preserved (Sangeetha and Abraham, 2008). Since precipitation is frequently used to purify enzymes, this technology offers the possibility of using semipurified enzymes as starting material, thus reducing costs. In addition, multiple enzyme activities can be simultaneously captured in such aggregates (combi-CLEAs), for cascade or non-cascade conversion (Dalal et al., 2007).

To exploit to its full the simplicity and robustness of CLEAs technology, several key issues need to be resolved, including how to control the particle size of the enzyme aggregates without causing significant diffusion constraints, how to avoid the dramatic modification of some essential e-amino groups by glutaraldehyde (which results in CLEAs with a significant loss of biological activity), and how to produce aggregates stable at basic pHs. Advance in the above critical questions have been made since the first paper describing CLEAs (Cao et al., 2000). These include the use of sodium borohydride in sodium bicarbonate buffer at pH 10 to reduce the Schiff base formed after cross-linking with glutaraldehyde (Wilson et al., 2004), the use of alternative crosslinking agents, such as dextran-polyaldehyde (Mateo et al., 2004) or bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a protein feeder (Shah et al., 2006) to prevent glutaraldehyde inactivation, and finally the use of longer vortexing periods (about 1 h) to recover the enzyme activity lost during the centrifugation and cleaning steps needed to prepare CLEAs, which results in large aggregates due to the low compression resistance of CLEAs (Wang et al., 2010). These last mass transfer limitations may increase when co-aggregation with BSA is used, since the internal structure of the aggregates is disturbed, resulting in narrower channels that limit the diffusion of the substrate thought the CLEAs (Cabana et al., 2007).

In this context, special attention should be paid to the two new methods developed to reduce the diffusional limitations of CLEAs. When the substrates of an enzyme are macromolecules, porous cross-linked enzyme aggregates (p-CLEAs) are prepared by adding starch as a pore-making agent, which is latter removed by a-amylase (Wang et al., 2011). In the case of small substrates, our group has described the use of a commercial cell disruptor (FastPrep ®, www.mpbio.com), based on a precession movement to recover all the enzyme activity of an acetyl xylan esterase in a few seconds (Montoro-García et al., 2010). This equipment produces a high- speed movement in all directions (vertical and angular motion), which causes cell disruption as a result of the collision between cells and beads in the reaction tube. The effectiveness of the cell disrupting process depends on the rate of the collision and the energy of the impact, which are functions of the speed settings (range, 4.0–6.5 m/s) and the specific gravity of the bead material used. The rate of collision is proportional to the speed, while the energy of impact is proportional to the square of the speed (Müller et al., 1998). In the case of CLEAs, their solid aggregates act as a dispersing material pulverizing each other in a short period of time (30 s) without the need for glass beads.

In order to expand the general use of such FastPrep-CLEAs (FP-CLEAs) in biocatalysis, this methodology was applied to recover the activity of N-acetyl-D-neuraminic acid aldolase (E.C. 4.1.3.3., NAL), a model enzyme that shows all the main characteristic that need to be solved to produce CLEAs. Its activity decreased to 51% after protein crosslinking (0.5% glutaraldehyde) for 5 min, when crosslinked inclusion bodies (CLIBs) were formed (Nahàlka et al., 2008). This severe drop in activity could be due to the fact that the catalytic amino acid (lysine) in this aldolase is modified, as it has been described for nitrilase CLEAs, where its modification by glutaraldehyde lowered the activity to 49% (Mateo et al., 2004). In addition, free NAL is used industrially at basic pHs (where standard CLEAs are not stable) for the condensation of pyruvate and N- acetyl-D-mannosamine (ManNAc) into N-acetyl-D-neuraminic acid (Neu5Ac), an advanced intermediate for obtaining GlaxoSmithK- lime’s antiviral Relenza® (Liese et al., 2006).

2. Methods

2.1. Materials

Pure recombinant Lactobacillus plantarum WFCS1 N-acetyl-D-neuraminic acid aldolase (LpNAL) with the 10-histidine C-terminal extension of pET-52 (Novagen, USA) was produced from Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLys cells (Novagen, USA) in three simple purification steps, as previously reported (Sánchez-Carrón et al., 2011). Sugars were from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). High purity glutaraldehyde (BioChemika) and ammonium sulfate (BioUltra) were obtained from Fluka (Madrid, Spain). Other reagents were from Sigma (Madrid, Spain).

2.2. CLEAs production

Aggregation tests with ammonium sulfate and the following steps were carried out at 4 °C by adding to 1 mL of a 10 mg/mL pure LpNAL in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.5, the required volume of saturated ammonium sulfate solution to bring the mixture to the desired degree of saturation with the salt. Pilot aggregation tests with acetonitrile or with tert-butanol (final concentrations up to 90% v/v) were carried out in the same way, except that cold solvent was added. After 1 h, the appropriate amount of a freshly prepared 25% (v/v) aqueous solution of glutaraldehyde was stirred into the suspensions to attain the desired concentration of the dialdehyde (concentrations tested, 0,2%, 0,5%, 1% or 2% glutaraldehyde). At various times after the addition of the glutaraldehyde, 100-ll aliquots were suspended in 900 ll of 20mM potassium phosphate pH 7.5 and were centrifuged (16,000g x 2 min), after which the enzyme activity in the supernatant and in precipitates was determined.

Test assays yielded active aggregates when using ammonium sulfate at 90% saturation and a 4-h cross-linking period with 1% glutaraldehyde (AS-CLEAs). At the end of the cross-linking period the entire suspension was centrifuged (16,000g x 2 min), washing the precipitated CLEAs three times by repeated cycles of suspension in 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.5 and centrifugation.

Sodium borohydride CLEAs (SB-CLEAs) were prepared as above, except that at the end of cross-linking step the whole reaction volume was doubled with 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate buffer pH 10, and during 30 min, 1 mg/mL of NaBH4 was added at intervals of 15 min (Wilson et al., 2004). The resulting CLEAs were washed and stored as AS-CLEAs.

Finally, BSA-CLEAs were formulated by slowly adding ammonium sulphate at 90% saturation to an LpNAL solution (10 mg/ mL) containing 2 mg/mL of bovine serum albumin under stirring conditions and a 4-h cross-linking period with 1% glutaraldehyde. Then, the whole reaction volume was treated with sodium borohydride as described for SB-CLEAs. All the preparations of the different CLEAs described above were stable for several weeks when stored at 4 °C.

2.3. Enzyme assays

For the standard assay of the synthetic activity of N-acetyl-D-neuraminic acid aldolase, i.e., obtaining Neu5Ac from pyruvate and ManNAc, the enzyme (generally, 0.1 mg/mL of CLEAs) was incubated at 37 °C with the above substrates at the indicated concentration of 100 mM ManNAc and 30 mM Pyr in 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.5. The reaction was stopped by centrifuging out the CLEAs (16,000g x 2 min). The sample from the supernatant were subjected to normal-phase HPLC (LC-20A, Shimazu) using an AMINO-UK column (Imtakt Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), a mobile phase consisting of 58% acetonitrile–42% 50 mM ammonium acetate and a flow-rate 0.4 mL/min at 60 °C. The elution profile was monitored both at 210 nm and with an ELSD-II detector (Shimadzu, Japan). In these conditions, the retention time (Rt) for Neu5Ac and ManNAc were 10.34 and 4.22 min, respectively. One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to synthesize 1 lmol of Neu5Ac per minute under the above conditions (Sánchez-Carrón et al., 2011). Enzymatic activity was obtained from three repeated experiments.

2.4. Scanning electron microscopy of CLEAs

Droplets from CLEAs suspensions were placed on moist filter papers and dehydrated serially (10 min, each step) by passage through a graded series of acetone solutions (30%, 50%, 70%, 90% and 100%) and dried at the critical point of CO₂ (Montoro-García et al., 2010). After gold sputtering, the samples were visualized with a Jeol T6.100 (Japan) scanning electron microscope (SEM) operated at 15 kV.

2.5. CLEA dispersion and sizing of the resulting particles

Two methods were used for the disruption of the aggregates. One approach, which is widely used, consisted of vortexing at medium speed with a Heidolph (Germany) Reax Control vortex. In the other (novel) approach, the CLEAs were subjected to reciprocating mixing using a FastPrep-24 sample preparation system (M.P. Biomedicals), CA, USA) at a setting of 6.0 m/s (Montoro-García et al., 2010). The degree of dispersion attained by both procedures was monitored by bright-field optical microscopy at a final enlargement of 40x, taking digital images that were analyzed planimetrically by image processing (MIP 4.5 image analysis software, Digital Image System, Barcelona, Spain).

2.6. Enzyme stability assay

The pH-stability was monitored by incubating the enzyme (either in soluble or in CLEA form) in a solution of 20 mM glycine buffer pH 9.0 at 50 °C, taking samples after the periods of time specified to determine enzyme activity in the standard assay at 37 °C, using ManNAc and pyruvate as substrates. In a similar way, the thermal stability was recorded by incubating the enzyme (in a free and aggregates form) in a solution of 20 mM glycine buffer pH 9.0 at the indicated temperatures (40–80 °C). After cooling, enzyme activity was determined in standard assay at 37 °C.

2.7. Computer analysis

Lysines and the Grand average hydropathicity index (GRAVY) of LpNAL and BSA were calculated using the ProtParam tool from Expasy Proteomic server (http://www.expasy.org/tools/protpa- ram.html). Negative GRAVY values indicate hydrophilic proteins (Kyte and Doolittle, 1982).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Optimization of CLEAs production

Pure L. plantarum N-acetyl-D-neuraminic acid aldolase (LpNAL) was used for preparation of the aggregates, since this enzyme has great potential as a biocatalyst due to its high stability at alkaline pHs, its high over-expression in E. coli and its simple purification procedure (Sánchez-Carrón et al., 2011). In a preliminary screen to select a suitable agent for protein aggregation, three different substances were tested up to 90% concentration, either to change the hydration state of the enzyme molecules (ammonium sulfate) or to alter the electrostatic constant of the solution (acetone and acetonitrile). After 1 h, the appropriate amount of glutaraldehyde (0.2–2%) was added, and the sample was diluted 10-fold in phosphate buffer and centrifuged to prove that no substantial activity remained in the supernatant after 4 h crosslinking with any of the treatments. Only ammonium sulfate preserved the 40% of enzyme activity in the resulting CLEAs (AS-CLEAs) after 60-min vortexing (Table 1), whereas organic solvents eliminated the activity, pointing to a solvent-triggered denaturing effect.

Similar findings have been reported for other CLEAs (Gupta et al., 2009; Hara et al., 2008; Montoro-García et al., 2010), where ammonium sulfate was also the selected precipitant.

In order to improve not only this low amount of recovered activity but also the stability of the above AS-CLEAs, sodium borohydride (1–10 mg/mL, SB) and BSA (1–10 mg/mL) were used. The use of SB resulted in a 16% increase in activity, reaching 56% (SB-CLEAs), when the optimal SB concentration was used (1 mg/mL) (Table 1, vortex column). In addition, co-aggregation of LpNAL with BSA followed by SB treatment (BSA-CLEAs) led to a twofold increase in activity, which reached 79% (Table 1, vortex column), which represents almost a 30% increase compared with the data obtained with E. coli NAL during its immobilization as cross-linked inclusion body (CLIBs) (Nahàlka et al., 2008). This increase in activity is similar to that described for aminoacylase, when BSA was chosen to increase the content of lysine residues and the consequent cross-linking efficiency (Dong et al., 2010). However, in the case of LpNAL the beneficial effect of the BSA seems to be due to the protective effect of the catalytic residue (lysine) rather than the lack of lysines, as has been described for nitrilase (Mateo et al., 2004) and penicillin acylase (Mateo et al., 2004). In fact, LpNAL has 24 lysines (7.7% of the protein resides) equally distributed through its sequence, so, the additional 66 lysines contributed by BSA basically prevents any extensive intramolecular crosslinking. The latter benefit of BSA contrasts with the fall in activity described for laccases in the presence of BSA (Cabana et al., 2007; Matijosyte et al., 2010), which was explained by mass transfer limitations (Cabana et al., 2007). In order to test whether such limitations occurred in the three different LpNAL CLEAs described in this paper, they were subjected to different mixing periods in two disaggregating devices (vortex and FastPrep). Table 1 shows that the use of FastPrep, first described by our group in the production of CLEAs (Montoro-García et al., 2010), was the best disaggregating system for all three CLEAs used, not only because of the short time required to reach maximal activity, but also due to the high level of recovery achieved. This FastPrep effect was more evident when a less sophisticated methodology was used to produce the aggregates. The fact that AS-CLEAs activity increased by 34% with FastPrep, compared with the 3% increase displayed by BSA-CLEAs, indicates the greater flexibility of the latter CLEAs resulting form the use of BSA as a proteic feeder (Shah et al., 2006) (see below, Section 3.2).

Planimetric analysis of the different aggregates also showed the influence of the time and dispersing device used (Supplementary Fig. S1). All mechanical treatments fragmented the CLEAs into particles, but most of the aggregates after 30-s vortexing (Fig. 1, black bars), were distributed in particle sizes up to 1000 μm², while 11% were larges (reaching 5000 μm²). After 1-h vortexing (Fig. 1, light grey bars), 60% of particles were in the 50–500 μm² range, whereas after 60-s of FastPrep treatment (Fig. 1, dark grey bars), 86% of particles were in the smallest range (0–50 μm²).

The last treatment, which is also the one that yielded the maximal recovery of the activity, clearly does not disturb the individual CLEAs, and, hence, the enzyme structure (as is evident from the SEM analysis, see below), preventing that particle from being compressed close together with concomitant mass-transport limitations. Similar results with FastPrep were also reported for acetyl xylan esterase CLEAs, although the particle size obtained was slightly greater, in the 0–149 μm² range (Montoro-García et al., 2010). Thus, it is clear from Table 1 and Fig. 1 that the FastPrep system could be of general application to produce efficient CLEAs, regardless of the protocol used to prepare them, and only CLEAs produced with this system were used in the rest of the present work.

3.2. Structure of FastPrep-CLEAs

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of the FastPrep-CLEAs produced in this paper revealed amorphous structures which differed depending on the protocol used. Thus, the CLEAs obtained with ammonium sulfate (AS-CLEAs) formed less structured and more coarse-grained aggregates (Supplementary Fig. S1a) than those formed by ammonium sulfate and sodium borohydride (SB-CLEAs) (Fig. S1b), whereas in the presence of BSA (BSA-CLEAs), they were organized as a network of 'branches' separated by pores, with a spongy and ‘holey’ morphology (Fig. S1c), which maximizes the catalyst surface available for reaction, while minimizing the diffusion effect within the catalyst, as has been previously described for hydroxynitrile lyase (Cabirol et al., 2008). These images clearly show the transition from the "classical chemical aggregates" of AS-CLEAs, previously reported in the literature (Tyagi et al., 1999), to a uniform porous mesh (BSA-CLEAs), which is somewhat between the ball-like structure appearance (type 1) and the less structured form (type 2) described by Schoevaart et al. (2004). These closely related type 2 CLEAs of Fig. S1c are produced in aggregates with a hydrophilic nature (Schoevaart et al., 2004), such as those containing LpNAL and BSA, which both have a clear negative Grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) number (-0.301 and -0.429, respectively).

3.3. Kinetic characterization of FastPrep-CLEAs

The catalytic activity of the three different FastPrep-CLEAs produced in this paper was investigated over a wide pH range (Fig. 2a). All the CLEAs exhibited a broad bell-shape pH dependence of the catalytic activity, similar to that seen for free enzyme (Sánchez-Carrón et al., 2011), but with a pH shift towards alkaline, with an optimum of pH 7.5 in contrast to the pH 7.0 of free enzyme. This shift could have resulted from the change in acidic and basic amino acid side chain ionization in the microenvironment around the active site, which was produced by the freshly produced interaction between basic residues of the enzyme and glutaraldehyde during cross-linking, as has been previously described for tyrosinase (Aytar and Bakir, 2008), subtilin (Sangeetha and Abraham, 2008) and acetyl xylan esterase (Montoro-García et al., 2010). In addition, the stabilizing effect of BSA (Fig. 2a, open squares) and sodium borohydride (Fig. 2a, filled squares) compared with ammonium sulfate alone (Fig. 2a, open circles) was more evident at alkaline pHs, giving rise to a fully active catalyst at pH 9.0, which is one of the demands for the chemoenzymatic synthesis of Neu5Ac from the inexpensive N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (Liese et al., 2006).

In addition, the biocatalyst has to be stable at such alkaline pH values, as is seen from Fig. 2b, where it is clear that only BSA-CLEAs (Fig. 2b, open squares) were as stable at pH 9.0 as the free enzyme (Fig. 2b, filled circles), and more stable than the SB-CLEAs (Fig. 2b, filled squares). The standard AS-CLEAs were clearly not stable at such pHs (Fig. 2b, open circles). No thermal stability improvements between free and BSA-CLEAS due to cross-linking were observed (data not shown), since NALs are very thermostable proteins with melting points (Tm) of about 74 °C at pH 9.0 (Sánchez-Carrón et al., 2011) and an optimal temperature about of 70–80 °C (Aisaka et al., 1991).

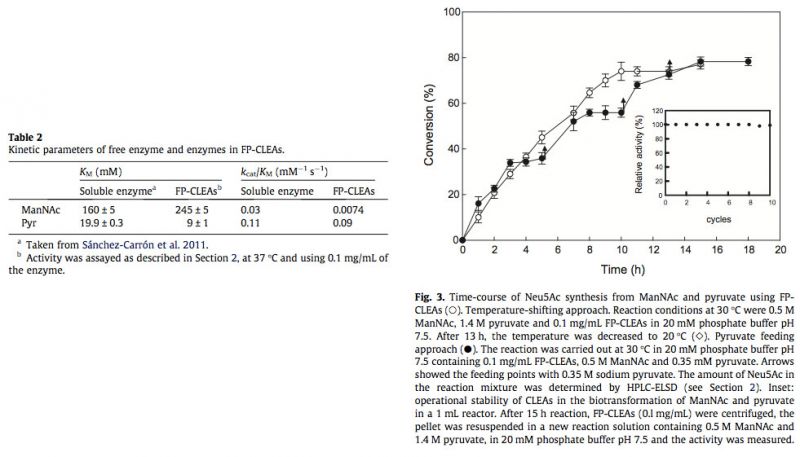

The kinetic parameters for the synthetic activity were also investigated with the best FastPrep-CLEAs obtained with BSA and SB (FP-CLEAs) at different ManNAc and pyruvate concentrations, and compared with free enzyme (Sánchez-Carrón et al., 2011). For both substrates, Michaelis–Menten type kinetic behaviour was observed for the CLEAs. As shown in Table 2, the apparent KM for immobilized enzyme was 1.5-fold higher for ManNAc than for free enzyme, whereas it was 2.2-fold lower for pyruvate. This differential change in affinity has also been described for the affinity of acetyl xylan esterase for 7-ACA and cephalosporin-C (Mont- oro-García et al., 2010), but there seem to be no clear rule, since both increases (Montoro-García et al., 2010; Shah et al., 2006) and decreases (Aytar and Bakir, 2008; Sangeetha and Abraham, 2008) in KM values have been observed in different CLEAs. These data (Table 2) indicate that the interaction of enzyme and substrate was stronger in the case of pyruvate, and possibly, that molecular hindrances are involved in the case of ManNAc after cross-linking with glutaraldehyde. The latter reagent was also responsible for the decrease in the turnover and in the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) of the enzyme for both substrates (Table 2), clearly indicating an attack on the catalytic lysine of NAL. Nevertheless, and in spite of the values shown in Table 2, these CLEAs are of biotechnological relevance. The apparent KM for ManNAc is lower than that reported for the enzymatic synthesis of Neu5Ac, with a KM values of 402 mM (Kragl et al., 1991), which needs concentrations about 0.7 M to reach maximum activity. On the other hand, the lower KM of pyruvate is also advantageous, since a high pyruvate concentration in the solution after the bioconversion hinders product recovery, due to the fact that pyruvate and Neu5Ac exhibit similar pKa values in the region of 2.2 (Kragl et al., 1991), making a tedious ion-change chromatography step necessary (Sugai et al., 1995).

3.4. Potential production of Neu5Ac

3.4. Potential production of Neu5Ac

To investigate the potential of LpNAL CLEAs for the production of the Neu5Ac in aqueous medium, the condensation of ManNAc and pyruvate by FP-CLEAs was studied. In this enzymatic reaction, an excess of pyruvate over ManNAc is generally used to achieve high yield of Neu5Ac, because the equilibrium tends towards pyruvate and ManNAc (Keq, 28.7 M-1 at 25 °C) (Kragl et al., 1991). For this reason, the FP-CLEAs reaction was carried out at 30 °C with an almost threefold molar excess of pyruvate over ManNAc (1.4 M/0.5 M) to archive a high reaction rate. When the reaction was approaching its equilibrium point, after about 13 h (Fig. 3, open circles), the reaction temperature was reduced to 20°C (Fig. 3, open diamonds) to obtain 77% conversion. Fig. 3 also shows the comparison of the temperature shifting reaction with another reaction in which pyruvate (0.35 M) was fed three times after the equilibrium point was achieved at 5, 10 and 13 h (Fig. 3, arrows), respectively. In both cases, the same yield was obtained, indicating the advantage of the temperature-shifting approach due to its simplicity and no need for repetitive additions of pyruvate. In addition, the yield obtained with FP-CLEAs from ManNAc was higher than that obtained with commercial Neu5Ac aldolase (60%) (Sugai et al., 1995), but lower than that obtained with a 10-fold higher concentration of enzyme in a free form (Blayer et al., 1996), which clearly avoids the possibility of enzyme inactivation produced during longer periods of reaction, as a result of pyruvate degradation (Blayer et al., 1996).

Having demonstrated Neu5Ac production with LpNAL FP-CLEAs, their stability during multiple reuses was investigated, using the temperature-shifting approach. Typically, reactions (1 mL) reached completion within 15 h, and at least 10 cycles were possible without any significant loss of activity (Fig. 3, inset). Such stability is the same as that observed when Neu5Ac aldolase is used in an industrial process, with a known solid support like Eupergit-C (Mahmoudian et al., 1997) or when it is immobilized into cross-linked inclusion bodies (CLIBs) (Nahàlka et al., 2008). This strongly supports the value of using hardened CLEAs in combination with the FastPrep system for dispersion, to yield FP-CLEAs with excellent resistance to mechanical stress, allowing high recoveries of catalyst after many cycles of use. These ten cycles without loss of activity in CLEAs has also been described for lipase (Gupta et al., 2009), R-oxynitrilase (van Langen et al., 2005) and acetyl xylan esterase (Montoro-García et al., 2010), but contrast with the four reuses possible with hydroxynitrile lyase (Cabirol et al., 2008) or subtilisin (Sangeetha and Abraham, 2008).

4. Conclusions

The results presented here highlight the potential of using hardened CLEAs (BSA and sodium borohydride) for obtaining an advanced intermediate for the antiviral Relenza®, such as Neu5Ac. The combinations of such robust CLEAs with an efficient dispersing methodology (FastPrep) reduces to 30 s the time needed to produce highly active FP-CLEAs with strong operational stability at alkaline pHs, where the industrial enzymatic process is carried out. These findings open up new pathways for using FP-CLEAs in the sequential enzymatic reaction for producing Neu5Ac from inexpensive N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, catalyzed by N-acetyl-D-glucosaminine-2-epimerase and N-acetyl-D-neuraminic acid aldolase.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by Spanish grants from MEC-FEDER (BIO2007-62510) and from Programa de Ayuda a Grupos de Excelencia de la Región de Murcia, Fundación Séneca (04541/GERM/06, Plan Regional de Ciencia y Tecnología 2007– 2010). M.I.G.G. and A.S.C. are holders of predoctoral research grants associated to the above project from Fundación Séneca. G.S.C. is a holder of a predoctoral research grant (FPU) from Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Spain. We are very grateful to Sofía Jiménez García, a Research Support Staff member from the University of Murcia, for her technical support, and also to María García, María Teresa Castels and Fara Saez from the Servicio de Ayuda a las Cien- cias Experimentales (SACE, Murcia, Spain) for their help in SEM images.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2011.02.026.

References

Aisaka, K., Igarashi, A., Yamaguchi, K., Uwajima, T., 1991. Purification, crystallization and characterization of N-acetylneuraminate lyase from Escherichia coli. Biochem. J. 276, 541–546.

Aytar, B.S., Bakir, U., 2008. Preparation of cross-linked tyrosinase aggregates. Process. Biochem. 43, 125–131.

Blayer, S., Woodley, J.M., Lilly, M.D., 1996. Characterization of the chemoenzymatic synthesis of N-acetyl-D-neuraminic acid (Neu5Ac). Biotechnol. Prog. 12, 758– 763.

Cabana, H., Jones, J.P., Agathos, S.N., 2007. Preparation and characterization of cross- linked laccase aggregates and their application to the elimination of endocrine disrupting chemicals. J. Biotechnol. 132, 23–31.

Cabirol, F.L., Tan, P.L., Tay, B., Cheng, S., Hanefekd, U., Sheldon, R.A., 2008. Linum usitatissium hydroxynitrile lyse cross-linked enzyme aggregates: a recyclable enantioselective catalyst. Adv. Synth. Catal. 350, 2329–2338.

Cao, L., van Rantwijk, F., Sheldon, R.A., 2000. Cross-linked enzyme aggregates: a simple and effective method for the immobilization of penicillin acylase. Org. Lett. 2, 1361–1364.

Dalal, S., Kapoor, M., Grupta, M.N., 2007. Preparation and characterization of combi- CLEAs catalyzing multiple non-cascade reactions. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzyme 44, 128–132.

Dong, T., Zhao, L., Huang, Y., Tan, X., 2010. Preparation of cross-linked aggregates of aminoacylase from Aspergillus melleus by using bovine serum albumin as an inert additive. Bioresour. Technol. 101, 6569–6571.

Gupta, P., Dutt, K., Misra, S., Raghuwanshi, S., Saxena, R.K., 2009. Characterization of cross-linked immobilized lipase from thermophilic mould Thermomyces lanuginosa using glutaraldehyde. Bioresour. Technol. 100, 4074–4076.

Hara, P., Hanefeld, U., Kanerva, L.T., 2008. Sol–gels and cross-linked aggregates of lipase PS from Burkholderia cepacia and their application in dry organic solvents. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzyme 50, 80–86.

Kragl, U., Gygax, D., Ghisalba, O., Wandrey, C., 1991. Enzymatic two-step synthesis of N-acetyl-neuraminic acid in the enzyme membrane reactor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 30, 827–828.

Kyte, J., Doolittle, R.F., 1982. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157, 105–132.

Liese, A., Seelbach, K., Buchholz, A., Haberland, J., 2006. Processes. In: Liese, A., Seelbach, K., Wandrey, C. (Eds.), Industrial Biotransformations. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany, pp. 457–460.

Mahmoudian, M., Noble, D., Drake, C.S., Middleton, R.F., Montgomery, D.S., Piercey, J.E., Ramlakhan, D., Todd, M., Dawson, M.J., 1997. An efficient process for production of N-acetylneuraminic acid using N-acetylneuraminic acid aldolase. Enzyme Microbiol. Technol. 20, 393–400.

Mateo, C., Palomo, J.M., van Langen, L.M., van Rantwijk, F., Sheldon, R.A., 2004. A new, mild crosslinking methodology to prepare crosslinked enzyme aggregates. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 86, 273–276.

Matijosyte, I., Arends, I.W.C.E., de Vries, S., Sheldon, R.A., 2010. Preparation and use of cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs) of laccases. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzyme 62, 142–148.

Montoro-García, S., Gil-Ortiz, F., Navarro-Fernández, J., Rubio, V., García-Carmona, F., Sánchez-Ferrer, A., 2010. Improved cross-linked enzyme aggregates for the production of desacetyl b-lactam antibiotics intermediates. Bioresour. Technol. 101, 331–336.

Müller, F.M., Werner, K.E., Kasai, M., Francesconi, A., Chanock, S.J., Walsh, T.J., 1998. Rapid extraction of genomic DNA from medically important yeasts and filamentous fungi by high-speed cell disruption. J. Clin. Microbiol. 6, 1625– 1629.

Nahàlka, J., Vikartovská, A., Hrabárová, E., 2008. A crosslinked inclusion body process for sialic acid synthesis. J. Biotechnol. 134, 146–153.

Roessl, U., Nahálka, J., Nidetzky, B., 2010. Carrier-free immobilized enzymes for biocatalysis. Biotechnol. Lett. 32, 341–350.

Sánchez-Carrón, G., García-García, M.I., López-Rodríguez, A.B., Jiménez-García, S., Sola-Carvajal, A., García-Carmona, F., Sánchez-Ferrer, A., 2011. Molecular characterization of a novel N-acetylneuraminate lyase from Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Appl. Envirom. Microbiol, doi:10.1128/AEM.02927-10 [Epub ahead of print].

Sangeetha, K., Abraham, T.E., 2008. Preparation and characterization of cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs) of subtilisin for controlled release applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 43, 314–319.

Schoevaart, R., Wolbers, M.W., Golubovic, M., Ottens, M., Kieboom, A.P.G., van Rantwijk, F., van der Wielen, L.A.M., Sheldon, R.A., 2004. Preparation, optimization, and structures of cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs). Biotechnol. Bioeng. 87, 754–762.

Shah, S., Sharma, A., Gupta, M.N., 2006. Preparation of cross-linked enzyme aggregates by using bovine serum albumin as a proteic feeder. Anal. Biochem. 351, 207–213.

Sheldon, R.A., 2007. Cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAÒs): stable and recyclable biocatalysts. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 1583–1587.

Sheldon, R.A., 2010. Cross-linked enzyme aggregates as industrial biocatalysts. In: Shioiri, T., Izawa, K., Konoike, T. (Eds.), Pharmaceutical Process Chemistry. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany. doi:10.1002/9783527633678.ch8.

Sugai, T., Kuboki, A., Hiramatsu, S., Okazaki, H., Ohta, H., 1995. Improved enzymatic procedure for a preparative-scale synthesis of sialic acid and KDN. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 68, 3581–3589.

Tyagi, R., Batra, R., Grupta, M.N., 1999. Amorphous enzyme aggregates: stability towards heat and aqueous-organic cosolvents mixtures. Enzyme Microbiol. Technol. 24, 348–353.

van Langen, L.M., Selassa, R.P., van Rantwijk, F., Sheldon, R.A., 2005. Cross-linked aggregates of (R)-oxynitrilase: a stable, recyclable biocatalyst for enantioselective hydrocyanation. Org. Lett. 7, 327–329.

Wang, M., Qi, W., Yu, Q., Su, R., He, Z., 2010. Cross-linking enzyme aggregates in the macropores of silica gel: a practical and efficient method for enzyme stabilization. Biochem. Eng. J. 54, 168–174.

Wang, M., Jia, C., Qi, W., Yu, Q., Peng, X., Su, R., He, Z., 2011. Porous-CLEAs of papain: application to enzymatic hydrolysis of macromolecules. Bioresour. Technol. 102, 3541–3545.

Wilson, L., Betancor, L., Fernandez-Lorente, G., Fuentes, M., Hidalgo, A., Guisan, J.M., Pessela, B.C.C., Fernandez-Lafuente, R., 2004. Crosslinked aggregates of multimeric enzymes: a simple and efficient methodology to stabilize their quaternary structure. Biomacromolecules 5, 814–817.

Abbreviations: CLEAs, cross-linked enzyme aggregates; AS, ammonium sulfate; BSA, bovine serum albumin; SB, sodium borohydride; FP-CLEAs, FastPrep-CLEAs; Neu5Ac, N-acetylneuraminic acid (sialic acid); NAL, N-acetylneuraminate lyase; ManNAc, N-acetyl-D-mannosamine; Pyr, pyruvate; LpNAL, Lactobacillus plantarum NAL; 7-ACA, 7-aminocephalosporanic acid.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +34 868884770; fax: +34 868884147. E-mail address: alvaro@um.es (Á. Sánchez-Ferrer).

Все поля со звездочкой (*) обязательны для заполнения

Данное действие необратимо.

чтобы сделать работу на сайте еще удобнее!

С помощью личного кабинета Вы сможете:

- моментально получать счета на оформленные заказы;

- отслеживать статусы выполнения заказа по оплате, отгрузке, наличию товаров на складе;

- вести историю заказов, повторять заказы полностью или частично;

- выбирать персонального менеджера;

- формировать списки избранного среди товаров, справочных материалов и видео;

- делать заказ со страницы избранных товаров;

- экономить время при заполнении форм заказа по каталогам и регистрации на мероприятия.